I read two articles today back-to-back, though they came from different sources. They represented completely different world views and the conceptual distance between their respective disciplinary paradigms was breathtaking.

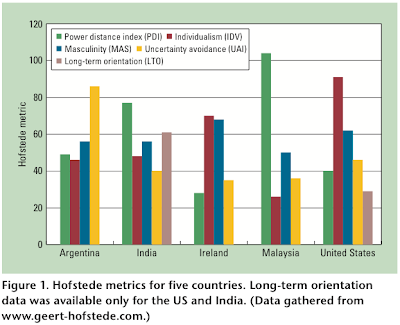

The first article came to me via a regular email from the IEEE Computer Society. It was by Phillip Laplante on cultural factors in software development. The article discusses Geert Hofstede’s work on five dimensions of social norms that could be used to characterize any culture. These dimensions are power distance index (PDI), individualism (IDV), masculinity (MAS), uncertainty avoidance (UAI), and long-term orientation (LTO). Each of these dimensions exemplified by choices in software process, for instance:

Are software engineers in low-LTO countries more likely to favor a code-and-fix approach to formal methods? Are software engineers in high-LTO countries more likely to favor spending more time on requirements engineering and less on testing?

Laplante is part of a task force charged with developing a professional licensure examination for software engineering. Consequently, he is wrestling with the question of whether it is reasonable to have the same exam in every region. His interest in Hofstede’s work is driven by the desire to be culturally sensitive. He gave data for five countries and asks questions such as:

Would software engineers in Malaysia (PDI = 104) use fewer techniques (such as reviews) that require higher management participation than in Ireland (PDI = 28)? How widely are group reviews (and the concomitant criticism) used in the US, where individualism is high (IDV = 91) versus in India (IDV = 48)?

I wasn’t especially interested in the work on the licensure exam, but I was intrigued by the Hofstede dimensions. I thought it was pretty interesting that culture could be distilled down to five dimensions and wondered how I could use this in my research.

The second article was forwarded to me by a colleague. It was a news article from the Program in Human Rights at Stanford University on a talk by a faculty member, Kentaro Toyama on ten myths about technology and development.

There is a lot of interest right now in humanitarian technology, and information and computational technologies for development (ICT4D). At the last CHI conference, there was a notable number of papers on this topic. Also, I co-authored a paper with Don Patterson on this topic.

Each one of Toyama’s myths resonated with me, so it’s hard to choose favorites, but here are a few.

Myth 3: ‘Needs’ are more pressing than desires: A high proportion of the income of the very poor goes on what Western observers might view as ‘luxury’ items: (music, photos, festivals & weddings) rather than ‘basics’ such as healthcare.

Myth 6: ICT undoes the problem of the rich getting richer: In contexts where literacy and social capital are unevenly distributed, technology tends to amplify inequalities rather than reduce them. An email account cannot make you more connected unless you have some existing social network to build on.

Myth 8: Automated is always cheaper and better: Where labor is cheap and populations are illiterate, automated systems are not necessarily preferable. Greater accuracy may be another reason to favor voice and human mediated systems.

Toyama caused me to seriously re-assess my reaction to the first article. There’s no way that Hofstede’s dimensions would help anyone trying to make their way in or design for the developing world that Toyama described. Laplante’s article belied an engineering mind set, where people are instruments, i.e. operators of machines and machine processes, who are in turn instruments of the machine. Toyama’s myths belied a humanist mind set, where people are fully-fledged autonomous individuals who live in a context.

As a positivist, Hofstede is trying to look for rules and generalizations about people. He’s trying to turn them into abstractions in a model, which can then be used to reason with. Furthermore, he’s turning the context into an input.

In contrast, Toyama is exquisitely sensitive to people as individuals in a context. Context is all. He’s trying to get you to really see what’s there, rather than your preconceived notions (or your model) tell you should be there.

It occurred to me if you take either point of view, you would never see the other, because of the blinders inherent in each. An engineering viewpoint is what gives rise to the misconceptions that are Toyama’s myths. By the same token, someone with a humanist viewpoint working in context-specific ICT4D would never arrive at a set of five dimensions for characterizing national cultures.

So, is one viewpoint (engineering vs. humanist) better than another? Part of me is very uncomfortable with looking at people and machines merely as instruments. I am much happier looking at people as loving-feeling-dreaming-jumping persons. But at the same time, I’m not sure that poets would design the best technology.

The solution is to be multi- or inter-disciplinary. Becoming steeped or indoctrinated into more than one discipline allows one to see the limitations and assumptions built in each disciplinary paradigm. I often say that asking someone to describe their own culture is like asking a fish to describe water. If you’ve never been out of your culture or water, you’d never see it.

This sentiment is echoed in a blog post that I also read today by Jim Coplien where he writes about the relationship between (software) engineering and the arts. “Cope” takes the middle ground and argues for the importance of both. I’ll let him have the last word.

You can’t study everything, but conquering complexity requires first a human outlook, then a social perspective, and finally a grounding in the arts. A good liberal arts education can raise your awareness about the human side of the world and about what matters to people. A grounding in user experience why the design of a computer interface (or any machine interface) is important and why it is hard. Psychology has everything to do with good computer system design. Literature and history can offer you cultural perspectives that make it easier to work into a shrinking world market. Architecture can help you articulate the complexity of design.